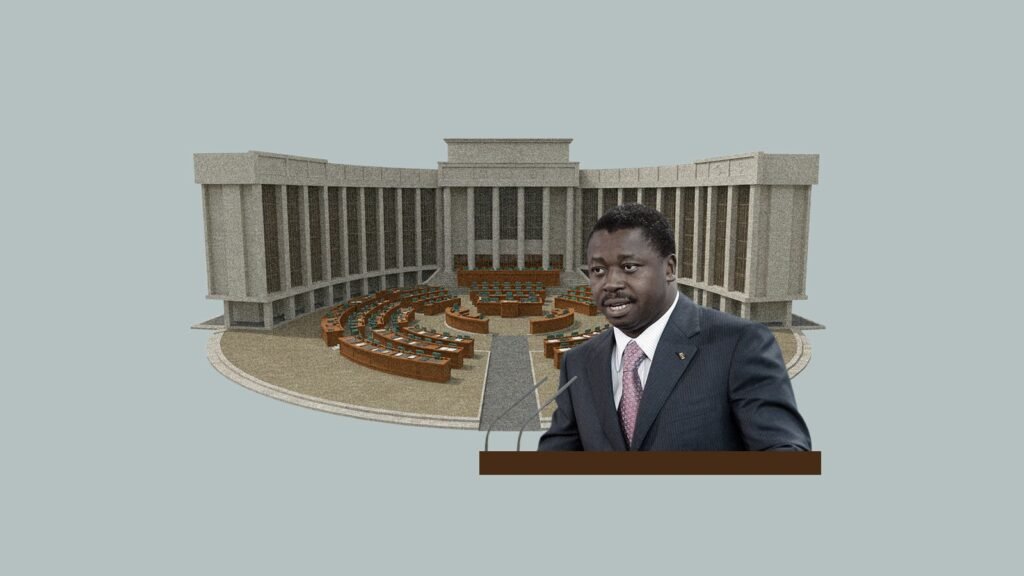

Faure Gnassingbé has never been a man to leave things to chance. In an unprecedented move, the Togolese president has officially appointed 20 new senators—10 men and 10 women—securing the final pieces of the country’s newly minted upper house of Parliament. The appointments follow the recent election of 41 senators, marking the Senate’s official debut under a controversial constitutional overhaul.

If the government’s narrative is to be believed, this marks a new era for Togo—a shift toward a parliamentary system under the Fifth Republic. A refined political model, a strengthened democracy, a future steered by collective governance. But for the opposition and civil society, the fine print reads more like a dynastic insurance policy, ensuring Faure Gnassingbé’s reign—already two decades long—does not end with his final presidential term in 2030.

Under the previous constitution, the clock was ticking. Togo’s head of state, like any other, could serve only two terms. But the Gnassingbé dynasty, which has held power since 1967, was never known for its embrace of political expiration dates. With the newly established parliamentary system, the need for direct presidential elections has vanished. Instead, a “President of the Council of Ministers” will hold executive power—an office with a six-year renewable term, tailor-made for continuity.

Critics say it’s a classic bait-and-switch. While the ruling Union for the Republic (UNIR) party insists this is a genuine step toward parliamentary democracy, opposition leaders and activists see a different picture: a power grab carefully wrapped in constitutional language. The loudest grievance? The people never got a say. No referendum. No national debate. Just a swift parliamentary adoption in April 2024, followed by its enactment on May 6.

For longtime opposition figures, this is the latest chapter in an old book. Since Faure Gnassingbé took over from his father, Eyadéma Gnassingbé, in 2005, he has mastered the art of political maneuvering. Now, with his party dominating both houses of Parliament—securing 108 out of 113 seats in the recent elections—the ability to dictate constitutional architecture is virtually unchecked. The Senate, meant to represent a democratic counterweight, appears poised to function as a rubber stamp.

But not everyone is wholly opposed to the new model. Christian Spieker, a former presidential hopeful, has expressed support for the idea of a parliamentary system—just not the version currently unfolding in Togo. He warns that without proper checks, Gnassingbé could easily slide into the role of Prime Minister or President of the Council, effectively maintaining his grip on power indefinitely.

As international observers weigh in, the opposition is urging external intervention. Civil society organizations are making noise, street protests are simmering, and diplomatic murmurs are growing louder. The big question remains: Will the new system bring true power-sharing, or is it merely a political facelift for the same old rule? Faure Gnassingbé may have traded the title of ‘president’ for a more parliamentary-sounding label, but power—real power—remains right where he wants it. And in Togo, that’s the only position that truly matters.